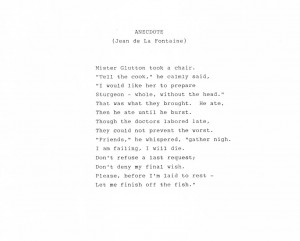

Translating verse is difficult enough; it’s harder to try to retain the rhyme and meter. Some paraphrase is always required, but it often comes closer to the original poem than a more literal rendition. It is, at any rate, a challenging writing exercise. Here’s my version of a verse by Jean de la Fontaine, from his first collection of tales in verse, 1665.

-

Categories

-

Archives

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

-

Admin

-

Search It!

-

Recent Entries

- Le Scat Noir’s Museum of the Inane3.31

- “Music From Elsewhere” in the Juilliard Store3.24

- Feeding Time3.17

- Bacchus With a Bowl3.10

- “Music From Elsewhere” in Brooklyn3.2

- Money Is the Only Thing2.24

- TYPO 92.17

- The Ball Game1.21

- The Virtuoso Parrot1.13

- “Music From Elsewhere” in New Paltz1.9

- Visit the archives for more!

Blogroll

© 2006–2007 Doug Skinner — Sitemap — Cutline by Chris Pearson

8 responses so far ↓

1 Mamie // Jun 13, 2014 at 9:16 pm

Poor Mister Glutton!

2 Doug // Jun 13, 2014 at 11:01 pm

Some people just don’t know when to stop.

3 Norman Conquest // Jun 14, 2014 at 9:47 pm

Nice!

4 Win // Jul 2, 2014 at 11:18 pm

I would agree that respect for meter and rhyme goes a long way toward bringing poetry over from one language to another. However I find that many translators of verse, especially poets, often stray too far from the literal meaning in their attempt to recreate the “feel” of a foreign poem.

I’m not very familiar with LaFontaine’s poems, but this one reminded me of an essay I read this afternoon, Three Forms of Sudden Death by Francisco Gonzalez-Crussi, in his book of the same name. One of the three forms he discusses is asphyxiation, of which the “cafe coronary” is one of the more morbidly entertaining, involving as it does the lodging of food in the pharynx (hot dogs are apparently a leading cause of such deaths, perfectly designed in scale and texture to do the trick). Gonzalez-Crussi doesn’t touch on death by overeating as LaFontaine does here, but in the course of emphasizing the fragility of human life (“fleeting and empty, like the froth formed at the surface of liquids that are shaken : buoyant one instant, vanished the next” – Ullage, anyone?) he quotes a pertinent and concise proverb that first appears in a work by the Roman scholar Varro: “Homo, bulla (man is a bubble). Don’t stand too close!

5 Doug // Jul 3, 2014 at 12:08 am

I find that it depends on the poem. I’ve been reasonably happy with my attempts to translate comic and narrative verse with the meter and rhyme, but found more serious poetry impossible. La Fontaine is well suited for the treatment. You can paraphrase a bit, and still stay close to the literal. And hot dogs should be avoided.

6 Win // Jul 3, 2014 at 12:07 am

Speaking of bursting, those of a republican and prudent cast of mind will find that an examination of the means of death of various British monarchs through the ages is both a caution and a delight. William the Conqueror, for instance, was so corpulent at the moment of his demise that his corpse burst during the efforts of his erstwhile servants to stuff him into his coffin. Henry I is another favorite; that fine fellow punched his ticket over a gargantuan plate of lamprey eels. King John had a sweeter tooth, and died under a load of peaches, pears and cider.

I recently discovered a wonderfully laconic account of the gluttonous end of a slightly less elevated member of the English elite in Austin Dobson’s Eighteenth Century Vignettes. His essay on Lady Katherine, second daughter of Henry Hyde, Earl of Clarendon and Rochester, who served as the model for the poet Matthew Prior’s Kitty, concludes with a sentence that I have always considered a perfect example of terse understatement, the kind of thing one would like to find at the end of a good novel: “She died in Savile Row in 1777, of a surfeit of cherries, and was buried at Durrisdeer.”

7 Doug // Jul 3, 2014 at 12:22 pm

Those monarchs! I have somewhere a typical dinner menu for the court of Louis XIV, and it’s alarming. I continue to be puzzled by all those fatal fruits. Swift blamed his broken health on apples; Diderot died from an apricot. What was it about the fruit? Was it the sugar?

8 Win // Jul 3, 2014 at 2:10 pm

Perhaps they should have been using juicers. You could, by the way, cook up a verse or two in French using the rhyme of Diderot and abricot…