In the interest of metaphysical and pataphysical confusion, some of my entries in the upcoming second volume of Le Scat Noir Encyclopaedia are fictional, and some are factual. This one, on a famous Parisian prankster, is factual.

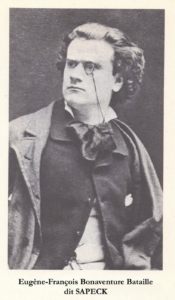

THE ILLUSTRIOUS SAPECK. Eugène Bataille (1853-1891), better known as the Illustrious Sapeck, is not to be confused with Eugène Battaille (1817-1882), the painter of historical and religious subjects, or with Eugène Bataille (1854?-?), the bass who enjoyed a long career with the Opéra-Comique and the Opéra de Paris.

This Bataille, as Sapeck, was admired by his colleagues as “the emperor of pranksters.” He sent out cards announcing his public appearances, in which he greeted the public in the gaudy costume of a “Hungarian composer,” or sat in a dogcart drawn by two horses, cheered on by hired street urchins. On one occasion, he shaved his head and painted it blue, explaining to the police that it “prevented dark thoughts.”

His exploits were inevitably ephemeral, but documented in the Bohemian press, often by his sometime accomplice Alphonse Allais. Like his operatic namesake, he was a gifted vocalist, equally adept at imitating dogs where dogs were prohibited, or at passing himself off as a “vocal inspector” at a girl’s school. Like his two-T namesake, he was also a painter, once giving a grocer a grisly sketch of a butchered rabbit, then sending his friends in to admire the priceless “original Sapeck.” He not only painted animals, but painted on them: the citizens of Honfleur were treated to a landscape of Normandy rendered in impasto on the curate’s donkey, and to the transformation of all the local horses into zebras.

He supplemented this career with cartoons for Scapin, Tout-Paris, La Lune Rousse, and other periodicals; illustrations for books by Coquelin Cadet, Léo Taxil, and others; and his own paper L’Anti-Concierge. His “Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe,” shown at the Arts Incohérents in 1883, probably inspired Duchamp.

His friends were baffled when he moved to Oise at 30 to become a prefectural counselor. Six years later, he was committed to a mental hospital, where he died at 38.

The following year, Taxil published his sensational anti-Masonic hoax, The Devil in the 19th Century, under the name of “Dr. Bataille,” in memory of his late collaborator, “the illustrious Sapeck, the prince of jokers in the Latin Quarter.”

2 responses so far ↓

1 Win // Oct 23, 2020 at 8:33 pm

Clearly this individual is a malicious fabrication indicative of the terminally decadent age we live in, however it is clear from Monsieur Bataille’s missives that we must paint our heads blue with all dispatch. I did so this past weekend, using a zero-volatile organic compound semi-gloss at $75 per gallon, and the results have been most edifying. I discarded my tinfoil hats in the East River last Sunday, wearing my best, and am happy to say that I have had no sleep since. Ah, bliss. Ah, joy of French poesy. Ah, fuck it, where did I put the remote?

2 Doug // Oct 25, 2020 at 7:42 am

I’m glad to see that Sapeck is still influencing the youth of today. His career was cut short too soon, but his work is still an inspiration.